Column | Max Bruinsma

In chemistry, a catalyst is a substance that enables or accelerates chemical processes without itself being absorbed into the process. A catalyst does not mix, but facilitates. In 2005, I curated an exhibition in Lisbon, which saw graphic designers as “catalysts” — as facilitators of social and cultural communication. In retrospect, I stretched the definition of the ‘neutral catalyst’ in that exhibition quite a bit. Everything in the show had an opinion. All the selected work represented a point of view — the designer interfered with his client’s message. No sign of the ‘noise-free transfer of information’ that the late Wim Crouwel would have liked to see!

Still, I maintain, even twenty years later, that designers initiate or accelerate processes. But they are never neutral. I once put it this way: you either sedate consumers, or empower citizens. Whatever you do as a graphic designer, if you do your job well, you amplify the impact and reach of a communication. That’s the ‘catalyst aspect’. The question is: what process do you foster?

That question is more urgent than ever in the past (over) half century. Then (in 1969), for example, there was the collective of designers that provided a catalytic impetus to the worldwide protest against the Vietnam War. The combination of a chilling dialogue about war crimes in Vietnam with its evidence — a photograph of dead women and children — amplified a shock wave of horror. “Q. And babies? A. And babies.” And now? The daily images of dead children and destroyed homes from Gaza, from Ukraine, from Sudan, from … seem to catalyze little more than awkward abhorrence.

The main difference between that half century ago and now, from a communication design perspective, is, of course, that communication processes have changed quite fundamentally, in volume and nature. A printed and globally distributed poster had an impact then that can hardly be imagined now. The confrontational and disruptive combination of text and image was new and disturbing then. Now it is the basis of every meme. And the catalyzing tools of artists and designers are now accessible to any computer owner, who can spread any hiccup worldwide with a mouse click. The catalyst has become part and parcel of the process.

But the question remains, though it has become a bit more complicated in the meantime: what process do you facilitate? In an in-depth essay in “Design for the Good Society”, the eminent design historian Victor Margolin gave a handle on that question. His concept of an “action frame” focuses on “the source of the values that guide our actions as well as the source of the worldviews that justify our behavior.” The Western action frame has brought us great things, but in the meantime it also leads to depletion of the earth’s resources, increasing inequality and crippling polarization. That action frame is no longer adequate, Margolin argued, and he was not alone.

The question then becomes: can you devise a new action frame? Can it be designed? According to technology philosopher Peter Paul Verbeek, in the same book as Margolin, it is not that simple. But in contemporary global politics, new action frames are rapidly being designed, with values and worldviews that superficially resemble the old ones — Democracy! Justice! Truth! — but which, on closer inspection, sometimes turn out to be the opposite: autocracy, inequality, ‘alternative facts’.

The design side of those new action frames has its roots in a very old tradition: rhetoric, the art of seductive form. That form often focuses on the immediate self-interest of the recipient (aka “target audience”). “Our people first” is a very trite, but also very effective variant. I don’t need a “Godwin” here to make a point; already the ancient Greeks understood the art of rhetoric, Aristotle substantiated the term, and a 15th-century Italian philosopher, Machiavelli, wrote a standard work on its political practice. That appearance is so important, more important it sometimes seems than content, means that all discussions of how we view the world and what happens in it are also, and profoundly, design questions. Influencing — and thus designing — “perception” is a crucial aspect of any society. And I daresay it is as important in our communication culture as the oxygen we breathe.

First Things First

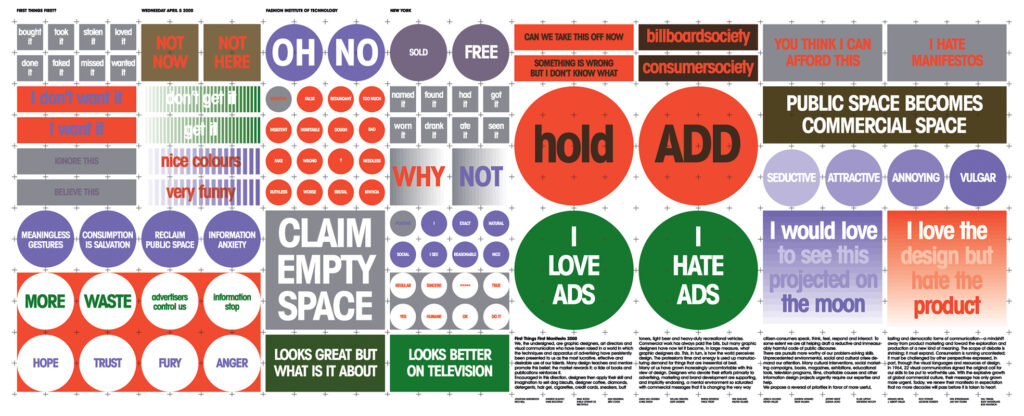

In 1964, British graphic designer Ken Garland initiated a manifesto, First Things First, in which he and his co-signers called on their colleagues to become more engaged in things worthy of their talent and craft: “We do not advocate the abolition of high pressure consumer advertising: this is not feasible. Nor do we want to take any of the fun out of life. But we are proposing a reversal of priorities in favour of the more useful and more lasting forms of communication. We hope that our society will tire of gimmick merchants, status salesmen and hidden persuaders, and that the prior call on our skills will be for worthwhile purposes.”

In 1999, as editor-in-chief of Eye magazine in London, I co-published a renewed appeal: “There are pursuits more worthy of our problem-solving skills. Unprecedented environmental, social and cultural crises demand our attention. Many cultural interventions, social marketing campaigns, books, magazines, exhibitions, educational tools, television programs, films, charitable causes and other information design projects urgently require our expertise and help.” The restatement of the then 35-year-old manifesto ended “in expectation that no more decades will pass before it is taken to heart.”

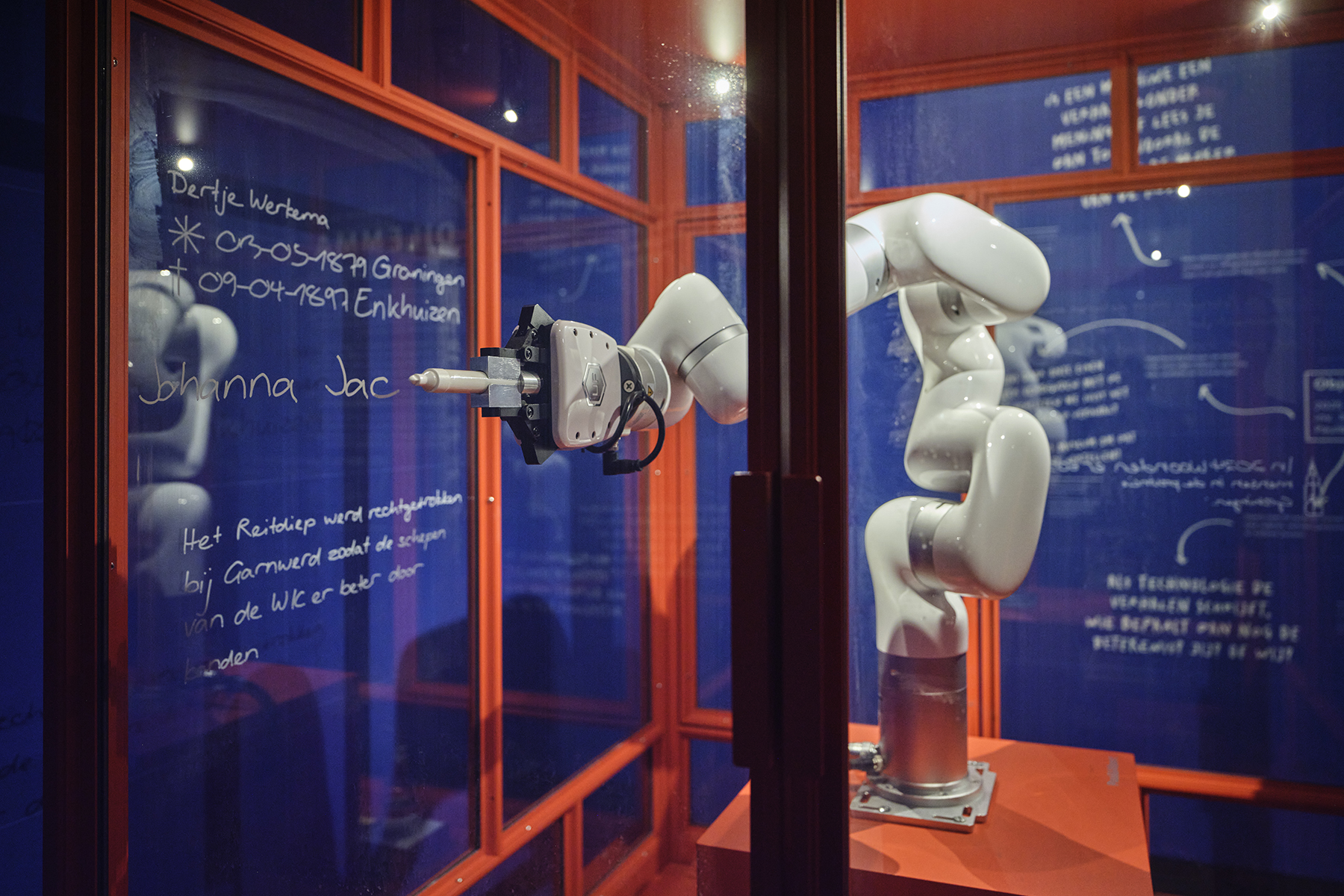

Well, that’s meanwhile also a quarter century ago (apart from a now dysfunctional website in 2018). And, as mentioned, the world has changed quite a bit since then again, although the challenges described in both manifestos have, basically, remained pretty much the same. But in a radically new context: what can professional designers still do when everyone has become a “designer”? Or when AI seems to be taking over their work? As far as I am concerned: by focusing less on virtuoso design (which, by the way, will remain a ‘unique selling point’ of professional designers for quite a while still, of that I am convinced), and more on designing the underlying processes. On the editorial process that facilitates the formal expression. How does something get to an audience? Through what channels? How “biased” are those? What is important and less important information? So a renewed focus on what Jan van Toorn once summarized it this way: “The origin and manipulative character of the message must be recognizable in its form.” Van Toorn meant: don’t hide behind your client. Even if you pretend to be neutral and only facilitate the process, every ‘problem solving’ has an ethical charge and meaning, which is also expressed in the form. Technology philosopher Verbeek added, “Designers who are ignorant of this fact, or disregard it, are operating in an immoral manner.”

I think it is time to take a fresh look at the First Things First manifesto, and to reissue it in a reinvigorated form, as a professional “action frame”. Preferably not in one newspaper (as in 1964), or six magazines (as in 2000), but globally, in all possible media. With a renewed perspective on the challenges and responsibilities of designers — and fundamentally the same message: everything designers do has a catalytic effect on the culture in which they work. Maybe third time’s the charm!

First Things First manifesto 1964

First Things First manifesto renewed appeal 2000