During Dutch Design Week, the symposium ‘The Future of Design Archives’ took place in the Van Abbemuseum. In a well-filled room, designers, archive specialists, policymakers and other stakeholders gathered for an afternoon devoted to the preservation, value and future of designer archives in the Netherlands. Read the summary of the discussions below.

Opening

Eline de Graaf, from the Network Archives Design and Digital Culture (NADD), opened the symposium. She explained how her love for archives began when she started working as a curator at the National Collection for Architecture and Urban Planning. ‘I thought, what is this? This is fantastic, we have to preserve this forever,’ she said of her first encounter with the collection of four million objects. But she discovered that there is no such repository for designers’ archives. ‘As a result, many archives are at risk of disappearing. That is a great pity and a very sad state of affairs,’ said De Graaf.

For this reason, the NADD was established in 2021 and has since grown into a network of more than seventy partners, ranging from archival institutions to design agencies and researchers. The NADD seeks to highlight the richness of designers’ archives and why they are worth preserving. ‘Together, we try to find answers to questions such as: where can archives go, where can institutions find each other, and where can designers find the institutions?’ explained De Graaf.

Timo de Rijk, director of the Design Museum Den Bosch and also chair of the Louis Kalff Institute, emphasised the importance of archives for the design profession. He pointed out the lack of resources and the need for shared responsibility. Without archives, he argued, the profession cannot exist in a historical perspective.

The practice of archiving

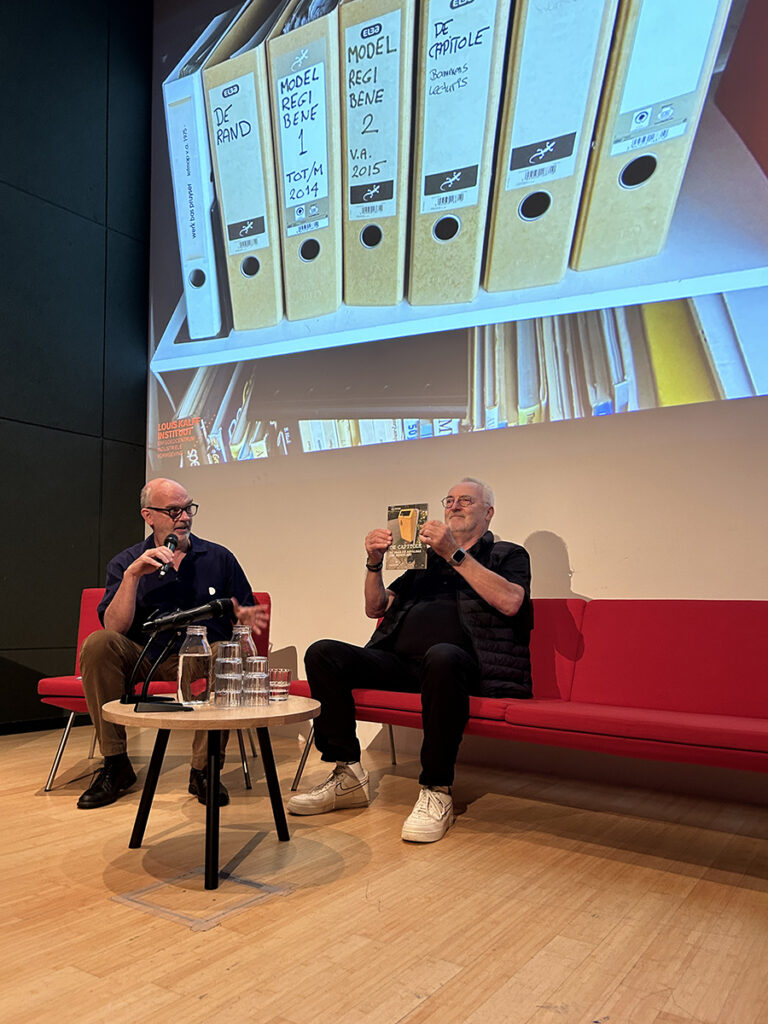

In a series of conversations, designers shared their personal experiences. Robert van Rixtel spoke with Bas Pruyser (1950), known for his street furniture and the Capitole litter bin. Bas spoke candidly about clearing out his archive. ‘I’m clearing out my design archive from 1973 onwards. Stacks of leaflets, tubes with hand-drawn sketches, boxes with scale models, prototypes, photographs and videos.’ The reason was practical: his study had been taken over by cots for his five children and six grandchildren. ‘I had to. It was no longer possible,’ said Pruyser about his urge to clear out. Yet he also felt sad: ‘I have some very nice 3D-printed waste bins… and then I think, who would still be interested in these?’

When asked whether he had contacted any archive institutions, Pruyser replied: ‘Well, no. Not really.’ His experience with the Arend archive had been disappointing: “After the office furniture company had fallen on hard times, no one was interested in looking at it at all. The Arend archive is the most beautiful archive in existence. It contains drawings by Kho Liang Ie, Friso Kramer and Wim Rietveld, still drawn by hand in perspective.‘ Ultimately, it is now stored in a warehouse belonging to Gispen,’ he said. ‘We tried to have it digitised, but the quote was 50,000 guilders. Then the director said: we’re not going to do that.’

Robert van Rixtel points to upcoming archives: ‘The great generation of Droogdesign is now approaching retirement age, and they are all over sixty. They themselves do not yet realise that they have archives that are valuable. So there will be a flood of important archives for which there is no solution.’

Bas proposes developing a plastic archive box with a screen and menu, so you know what’s inside: ‘As a designer, it really inspires me to design a nice archive box.’

Job Meihuizen spoke with Ineke Hans (1966), a renowned designer from a younger generation. She recognised the dilemma. ‘My problem is that I have quite a lot of space and I keep everything. It takes up a lot of space and that starts to bother me,’ she said. Ineke Hans not only keeps labeled boxes, but also many models and prototypes. She regularly uses her archive as a source of inspiration, but struggles with the question of what should ultimately be kept. She pointed out the importance of guidelines: “For me, it would be nice to know what you should actually keep and how you do that. It’s also nice to know whether it’s actually important that my archive is preserved or not. If there were some kind of signal saying, “Hey, Ineke, you’re on a list, don’t throw everything away,” that would make a difference in whether you do the whole tidying exercise or not.”

Eline de Graaf spoke with Floris Hovers (1976), a designer from a slightly younger generation. He explained how he mainly uses his archive for himself. ‘I’m a collector. I can never throw anything away.’ His 400-square-metre workshop is filled with models, prototypes and objects. ‘It often happens that I’m working on something and think: hey, I did that once, I must still have it somewhere.’ Hovers sees his archive partly as something that is already out there in the world: ‘Because there are collectors, people who have purchased your work, your archive is of course already out there in the world.’

He talked about his personal archive: “I have a wooden box that I once made myself. I still have it. And I’ve started keeping all my important things in it. Just personal stuff. Photos of girlfriends, letters, things. So it’s a kind of archive of my own personal life. If my children ever find it, I think they’ll have a lot of fun. You could also say, give all designers who need to archive their work one box, designed by Bas. And that’s it, everything has to go in there.”

When asked whether he had any hopes or expectations for his archive, Hovers replied: ‘You hope that people will say, that one specific thing created by Floris should be preserved. I would like it if a number of things were kept in a permanent place at an organisation, where you could easily find them again. I would think that would be really cool.’

Institutional challenges

The personal stories were followed by a panel discussion with Timo de Rijk, Miriam van der Lubbe (Dutch Design Week, designer) and Aukje Bolle (business director of Het Nieuwe Instituut). Van der Lubbe explained how her studio was one of the first to participate in the NADD Archive Project. ‘We have someone in the studio who brings us a number of boxes every week. It’s a hellish job,’ she admitted. She emphasised the importance of clear principles: “All boxes containing publications are excluded from the archive. Anything that we did not produce ourselves is discarded. However, we do keep a removal list.”

Van der Lubbe advocated for archives as tools, not as static storage facilities. ‘Het Nationaal Archief in The Hague is a good example. People, researchers and scientists visit there every day. You request a document and within twenty minutes it’s right in front of you. We should have something like that for the design world.’

Aukje Bolle explained why there is an extensive infrastructure for architecture, but not for design. ‘We are not an archive, but a collection, and we fall under the Heritage Act, not the Archives Act. That is very technical, but important,’ she said. ‘For architecture and urban planning, you cannot preserve the end products, so archives are important. For design, it is different.’ The NADD originated from the support function of Het Nieuwe Instituut, not from a collection task. ‘We are now trying to use the network and digital tools to provide insight into what is true, but there is still no central location for design archives.’

Bolle emphasised the importance of a collective approach: ‘We should all lobby together, and we are doing so, to advocate for the political choice.’ The NADD has a clear goal: ‘To ensure that at the end of the forty-year journey, cardboard boxes and Albert Heijn bags are not just left outside someone’s door, but that designers start thinking early on about what should and should not be archived.’

Mirjam emphasised that the field itself can also do more: ‘I think it’s everyone’s own responsibility to make a good start, at least. And at the same time, we also need to work together to create that critical mass so that our voice can be heard much more loudly.’ She called on designers to join forces and take a stand: ‘There is simply a huge gap here.’ Van der Lubbe concluded: “I would really like to call on all designers in the room to take a good look at the NADD website. See what they can do for you in terms of archiving your own archive. It contains lots of manuals and tips. You can really benefit from it.”

Discussion and questions from the audience

Critical questions came from the audience, including from Theo Groothuizen, former owner of Landmark. He asked why, after twelve years of discussion, it is still not possible to determine a course of action for design archives. Timo de Rijk explained that museums are often unable to manage archives due to their collection policy and lack of resources. ‘A museum does not have an archive, only an archive of itself, but collects a collection. If you offer models, they are interested, but they cannot do anything with an archive,’ said De Rijk.

Digitisation was also discussed. ‘The first things I took with me digitally from the office where I worked were no longer usable after a few years because the programme had been taken off the market,’ said an architect from the audience. Aukje Bolle acknowledged the problem: “We have started digitising the archive, but the media and file formats are quickly becoming obsolete. You have to keep up with the latest developments.”

Diana Janssen, director of the BNO, emphasised the importance of archive awareness among the new generation of designers: ‘The BNO is in frequent dialogue with educational institutions to ensure that a new generation of well-trained designers emerges. Our training courses include raising awareness of the importance of starting to set up your own archive as early as possible.’

Another important point was the use of archives. ‘In my opinion, the user is ultimately what you do it for,’ said Van der Lubbe. ‘But then you have to be able to explain clearly what is available and what its practical value is.’ There were also calls for greater collaboration with educational institutions to raise awareness of archives among young designers.

During the symposium, the tension between the wishes of designers and the demands of historians and archival institutions became clearly visible. Robert van Rixtel recounted his conversation with Ulf Moritz, who said he wanted to be remembered primarily as a fabric designer, while he would prefer that other, less special commissions not be preserved. Robert concluded: ‘If you are a designer and you are not yet dead, you have control over what is preserved and what is not, and how you want to be remembered. After your death, historians decide what happens to it.” This illustrates the difference in perspective: designers want control over their legacy, while historians prefer to preserve everything for future research. Aukje Bolle emphasised that as long as an archive is private, the designer is free to choose, but once it enters a collection, strict preservation rules apply. The question ‘what do you preserve, and who decides?’ therefore remains relevant.

Solutions and future

The symposium ended with a call to action. ‘We should all lobby to advocate for the political decision to give design a central place with the necessary resources,’ said Aukje Bolle. Van der Lubbe added: ‘The field itself can also do more. Designers need to join forces and take a stand.’

The afternoon concluded with practical tips: use the NADD manuals, start archiving early, collaborate and share knowledge. But the core of the message was clear: without structural, political choices and resources, a significant part of Dutch design history is at risk of being lost. As Eline de Graaf put it: “Archives are a deeply human expression of culture. We make art, we have culture and we collect. That’s what we do. But now we really need to start safeguarding it.”

Organisation symposium: Network Archives Design and Digital Culture (NADD)and Louis Kalff Instituut, the heritage centre for industrial design archives.

Photography: Dutch Design Daily