Longread | Pim van baarsen

Decolonization of the Future

What makes something valuable? Who decides which materials, techniques and knowledge get recognition, and which are ignored or exploited? These are questions that have occupied my mind for some time. As a designer, I see how design not only shapes products, but also systems and power relations. And when we look at how resources, traditions and ideas move through the world, we see that value is rarely determined neutrally.

During my time at Super Local, I worked on projects that focused on local craftsmanship, material innovation and circular thinking. But again and again, I saw that sustainability is not just about materials, but also about relationships and collaboration. My recent experience as an independent designer in Indonesia has only further deepened those insights.

LAMPOEP, an innovative lamp made from cow dung and tofu waste

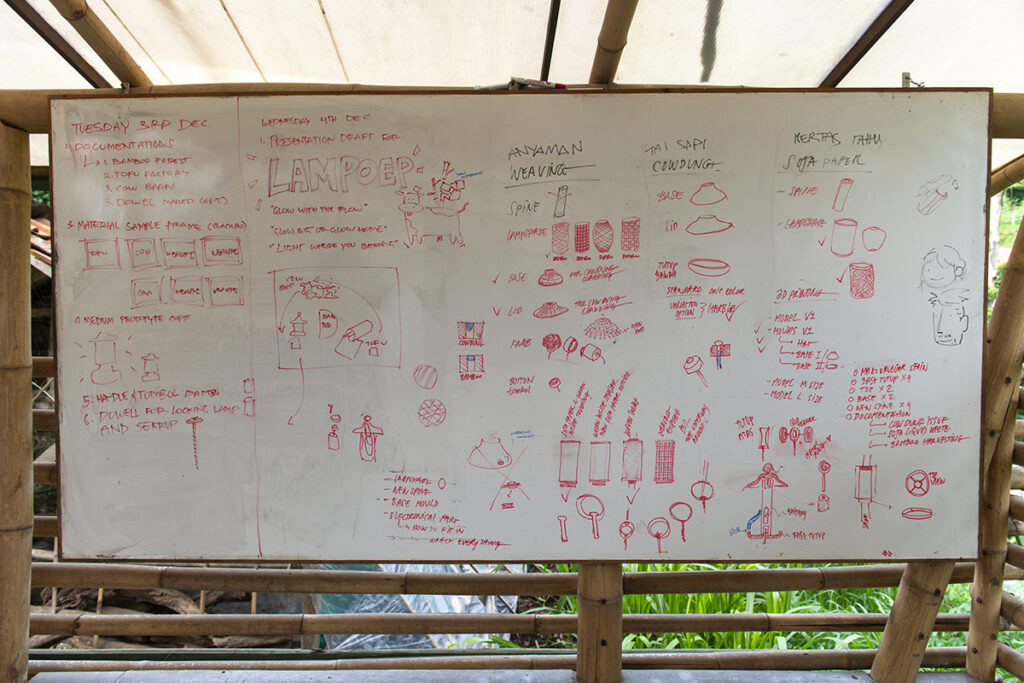

Since the winter of 2024, I have been working in Indonesia with Adhi Nugraha of Cowka, Ratna Djuwita (materials designer from Yogyakarta and founder of Mater Designlab) and Hilwa Azzahra (designer from Sulawesi) on a project in which we are repurposing cow dung and tofu waste into a wearable lamp. The basic construction consists of a fine weave of local bamboo – a traditional and indigenous material that shapes the product and literally connects the two waste materials. Both cow manure and liquid tofu waste are a growing environmental problem in Indonesia: they pollute ecosystems, degrade soil and pose a threat to people and nature. In this project, they are not seen as a burden, but as a valuable resource. The result is a lamp that is not only lightweight, aesthetic and circular, but also timeless in form and meaning – a local answer to a global problem.

What makes this project special is that it serves as a blueprint: a system approach that can be translated to other regions with similar challenges. The nanocellulose process, for example, is applicable to a variety of waste streams – including in the Netherlands, where we face manure surpluses and agricultural waste. By utilizing locally available materials and techniques, the project shows how waste materials can be transformed into high-quality materials from which unique products can be made. The project is currently on display at Erasmus House, the cultural department of the Dutch Embassy in Jakarta, and will remain there until May 2025. We also very much want to show it during Dutch Design Week 2025 – and are doing everything we can to make that happen.

The project symbolizes a different way of designing: locally rooted, internationally relevant and supported by equal collaboration. Too often we see a one-way street in which companies, brands and designers from the global north extract materials, techniques and knowledge from the global south – without considering the consequences. This is not only at the expense of ecosystems, through deforestation, pollution and the expropriation of land, but also of local communities, whose knowledge and traditions are taken over without recognition, cooperation or a fair distribution of value. This often lacks a deep interest in the origins and context, so this knowledge is not only exploited, but also undermined – losing the possibility of real impact.

But what if we turn that around? What if we recognize that solutions are not only created in European studios, but everywhere where people work on the future with care and skill? What if we actively make room for knowledge from the global south, not as exotic inspiration, but as equal input for innovation? Consider designers like Nifemi Marcus-Bello, who works from Lagos to create designs that are deeply rooted in the local context and do not conform to Western design standards. His work is both functional and empathetic, showing how social impact, cultural awareness and aesthetics can reinforce each other – from the inside out. Such examples show that the future of design is just as likely to be shaped in Lagos, Jakarta or Kigali as in Eindhoven or Copenhagen.

The project in Indonesia confirmed for me how powerful it can be when design emerges from a mutual exchange of knowledge, materials and context. It ties in with previous experiences in which I saw how indigenous communities in particular deal fundamentally differently – and often much more carefully – with value, waste and recycling than we are used to in Western industry. Decolonization in design means recognizing that progress does not come exclusively from the global North. It means recognizing that valuable innovations arise everywhere, often in the very communities we have too long seen as “disadvantaged. Indonesia was not a first introduction to that idea, but a deepening of that conviction.

What all these projects teach me is that sustainability is not only about materials, but also about relationships. If we want to be truly circular, we need to look beyond recycled raw materials or carbon footprints. We need to rethink how we produce, who we work with, who has the power in that process – as well as factor in the hidden impacts that often remain out of the picture. As Babette Porcelijn sharply demonstrates, the greatest environmental impact is often not in the use of a product, but in what precedes it: the extraction of raw materials, the production process and global transportation. As long as that impact remains out of the picture, it is impossible to speak of true sustainability.

The role of designers in system change

We live in a time when the world is changing rapidly and when political and social developments can sometimes be paralyzing. It can feel like the movement toward a more just, sustainable future is being slowed down – not only by fear and resistance, but also by larger powers that have an interest in the status quo.

But as designers, we have a unique power: We can see the dot on the horizon. We can visualize how things can be done differently, and bring people into that story. Not everyone sees or feels that future, and that’s understandable. Change is often abstract and elusive – but that makes it all the more important that we keep dreaming, keep imagining, keep building.

Gooda Gaado x Cowka

This project was developed as part of Design Matters Lab, an EU-supported program focused on advancing sustainable product development through collaborations between Indonesian and European designers. The program brings material-driven designers together with micro-factories to create groundbreaking solutions by utilizing alternative materials and developing meaningful products.

Ratna Djuwita, Hilwa Alifah Azzahra, and Pim van Baarsen are the Gooda Gaado Collective, a dynamic and innovative design team with diverse perspectives and skillsets, creating unique and impactful design solutions.

The collaboration of Gooda Gaado with Adhi Nugraha, and Cowka as the micro-factory, has been the key to the success of this project. The Cowka collection, which focuses on cow dung, was integral to the development of the lamp. Throughout the project, we have relied on Adhi’s expertise, his team, and the studio’s resources.

Photography: Pim van Baarsen